In the poignant short film, Fly in the Ointment (2015), real prisoner Peter Collins shares a raw, intimate account of his experience in punitive isolation. He talks of dreaming of his wife touching his arm and awakes to see a fly crawling over his skin. So starved of loving touch, he remains still as a rock as not to disturb the fly, and tries to sink back into the unreality where it’s his wife’s delicate fingers he feels. When the fly is attracted to a cut on his arm, he goes so far as smearing a drop of blood mixed in spit on his forearm to keep the flies attention. The honesty of the film gives a glimpse into the fragile state of mind that overcomes us when subjected to touch starvation, or ‘skin hunger’.

Our attention falls on contact especially during this time of mass isolation, where contact is scarce or unvaried. Our fundamental need for touch generally is satiated in a way that Peter Collin’s wasn’t, but we all share a subtle, constant desire for bodily contact. Dr John Reeves says “Touch is our first language and one of our core needs. The touch of a safe, trusted loved one can alleviate anxiety and promote a sense of well-being without doing anything else.”

In January I started a project focusing on touch. Early on I realised that I use contact with other people to ground myself when my mental health is particularly bad. It arises when I’m stressed, or depressed or even manic - a moment in time where someone clasps my wrist with a comforting firmness, and my attention, previously clouded and drifting, is drawn to something real and solid. It’s a coping mechanism called Mindfulness, taught in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, where you are told to truly focus on the senses (note what you can hear, 5 things you can see etc.) These actions ground us in the physical world and draw us away from problematic thoughts and emotions.

The problem with using interpersonal contact to ground you is that it heavily relies on other people consenting to such constant touch, which can often be met with resistance. It didn’t occur to my self-occupied brain that people are as repelled by unnecessary or unexpected contact as I am comforted by it. As someone with mostly introverted friends, I realised that I was invading a bubble and causing the same anxiety that I was seeking to relieve.

I was torn between the compulsion to touch and the self-disgust of inflicting anxiety: the duality of want and can’t have, being drawn to something but also repelled by it. The way to articulate this was through using disgust.

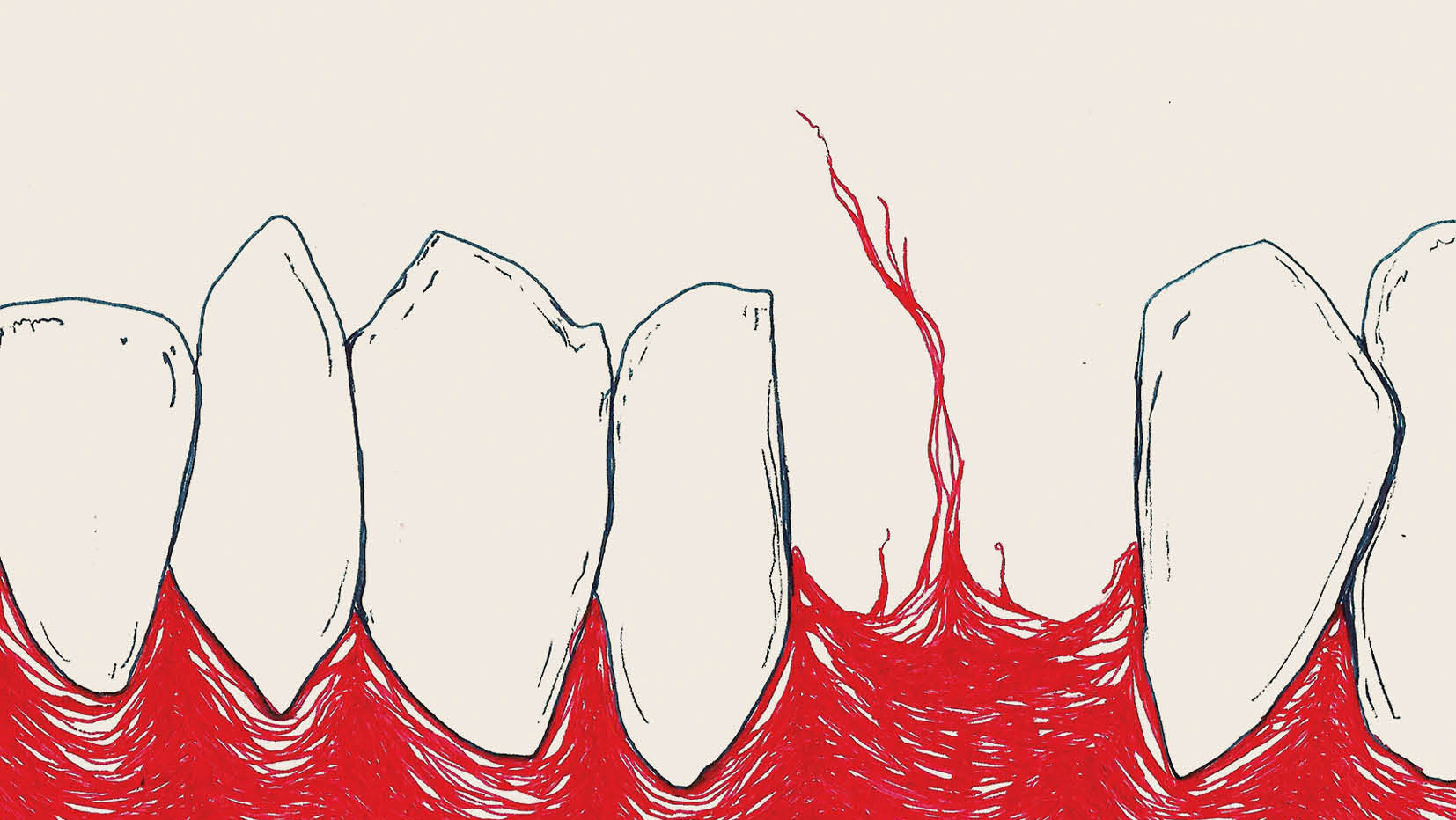

The connection between disgust and the body isn’t an unusual one - it’s easy to be put off by our own pinkish gums, wet insides, jagged nails and flaky skin - but bodily disgust is something that we can all empathise with. Which makes it an excellent topic for art.

Carolyn Korsmeyer believes that disgust is a valuable tool in creating compelling art, rather than the primitive response it’s dismissed as. She says in Savoring Disgust: The Foul and the Fair in Aesthetics (2011) that "Disgust is among the strongest of aversions, characterized by involuntary physical recoil and even nausea. Yet paradoxically, disgusting objects can sometimes exert a grisly allure, and this emotion can constitute a positive, appreciative aesthetic response when exploited by works of art -- a phenomenon labelled here ‘aesthetic disgust’." There’s grisly disgust in Fly in the Ointment, which is perhaps what makes it so compelling.

Animated short film, Teeth by Daniel Gray and Tom Brown, has a mundane grisliness to it. It follows a man’s lifelong relationship with his teeth; resenting them, losing them, and eventually coming to terms with dentureless gums in his old age. We can't all relate to his story, but we can relate to the wetness of a tongue exploring gums, the creak of a single tooth gnawing into wood, a serrated knife’s hitches catching a tooth edge one by one. It’s laden with moments that the viewer can feel, unsettlingly empathisable.

It seems one of the reasons disgust and art make such good companions is in our ability to empathise with other people's sensations, particularly the kind that make us uncomfortable. You don't have to have been punched in the face to wince when you see someone else get hit. No matter how emotionally empathetic a person is (or isn’t), most neurotypical people have a strong reaction to seeing pain. There is a specific area of the brain that’s activated both when we empathise with other people’s sensations and when we feel those sensations ourselves, and negative sensations (like pain and discomfort) have a particularly potent response.

Author Julia Armfield is skilful of particularly potent kinds of bodily disgust. In her collection of short stories, salt slow, she focuses on “the body as a locus of fear”. Armfield’s stories are disgusting but mesmerising. She leads the reader down a path partially blindfolded, able to catch glimpses of what is really happening behind the front of the story, but only when she leads you to the end do you realise the gross culmination of her tale. The anticipation leading up to the moment of disgust is enough to pull you in once more.

Her stories depict women often as the pinnacle of transformation, emotional and physical. In Mantis, a catholic school girl attempts to navigate teenagehood, boys and problematic skin (“not quite eczema but not quite acne either. Psoriasis or vitiligo or something."). She gradually flakes off skin, loses teeth and sheds hair to reveal an insect-like nature within. Armfield explains, “The transformation is a horror, of sorts, but it is also an emancipation—once freed from her physical strictures, the protagonist can act in a way that is natural to her (can do to a boy what a praying mantis would normally do to her chosen mate).” A disgusting process made way for a cathartic, emotional release.

Armfield's stories tune into a fear of transformation. There’s something unsettling about our bodies changing, especially unexpectedly - especially into something wrong. I remember waking one morning to see a tiny mole had appeared on my stomach. It was one of my first experiences of realising my body is not my own, just the space that I occupy, and something I have limited control over. I can move my arm but I can’t control the beating of my own heart, or stop my forehead wrinkling or my nails growing.

There will always be something unsettling about our bodies. There will always be disgust at seeing the parts we’re not meant to see, the blue-turning-red blood, the fork of a tooth’s root, our soft, delicate insides. Some will find it disgusting, some fascinating - and some will be able to toy the line between the two. But disgust and bodies go unsettlingly well together.